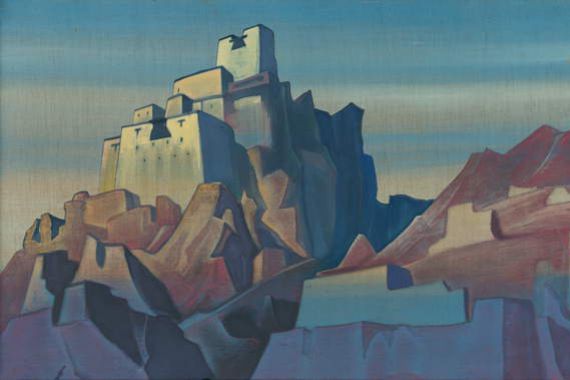

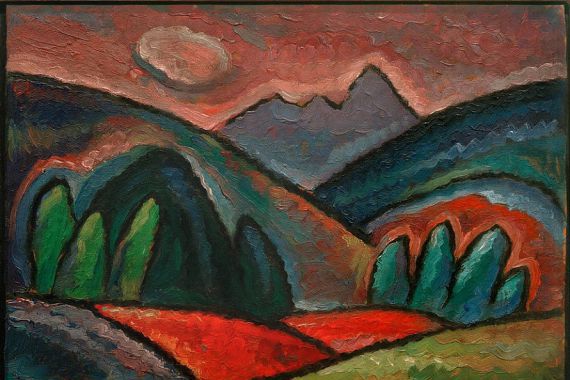

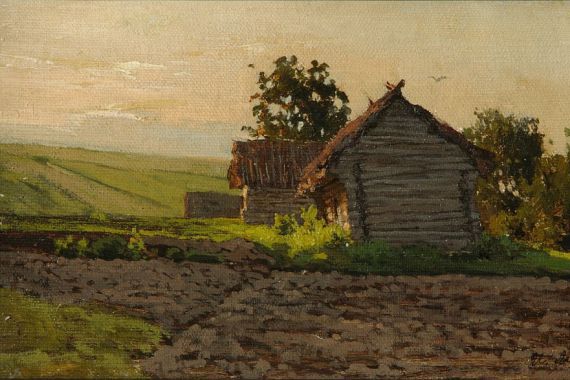

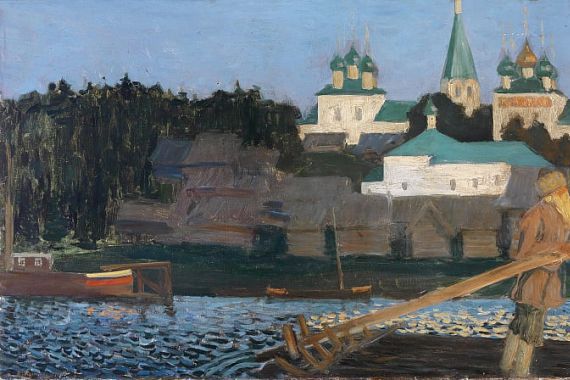

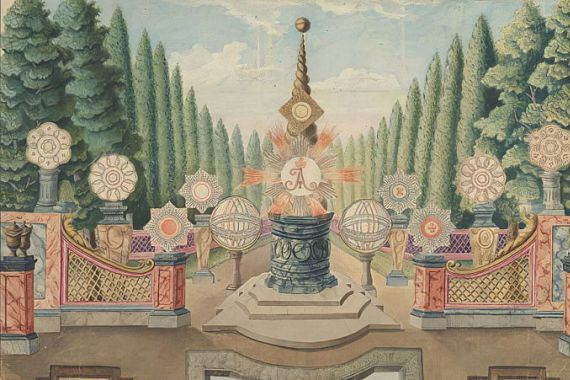

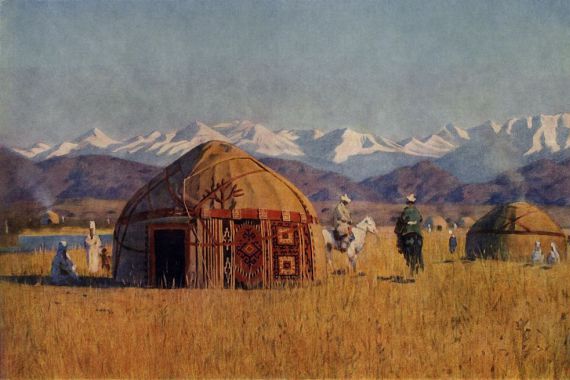

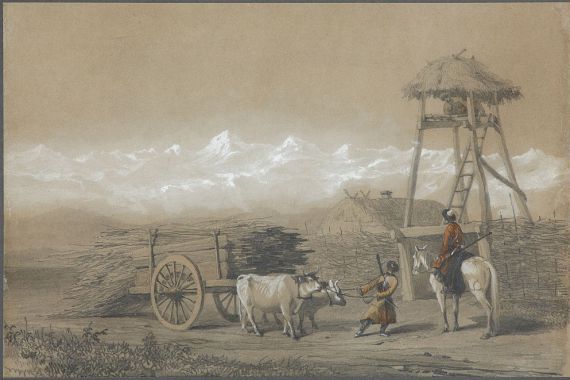

A soft mist lies over the endless expanses as I - a young painter driven by longing and curiosity - look at the Russian landscape for the first time. The air is permeated by a peculiar melancholy that covers the villages, forests and rivers like a veil. In Russia, it seems to me, art is never merely a reflection, but always a mirror of the soul, an echo of the mighty nature and the turbulent history. The colours I mix on my palette are heavy and rich, as if they wanted to capture the depth of the Russian earth - ochre, deep blue, the red of the setting sun. Here, where the winters are long and the summers are suffused with shimmering light, pictures are created that tell more than words ever could.

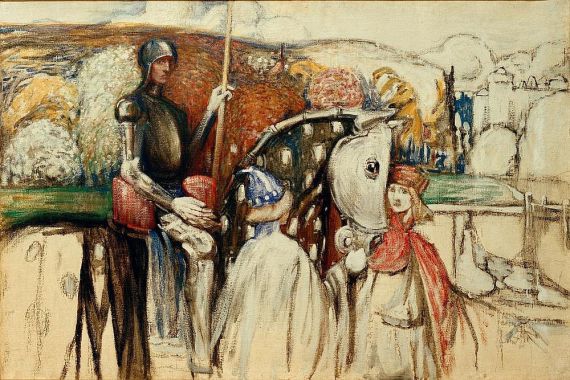

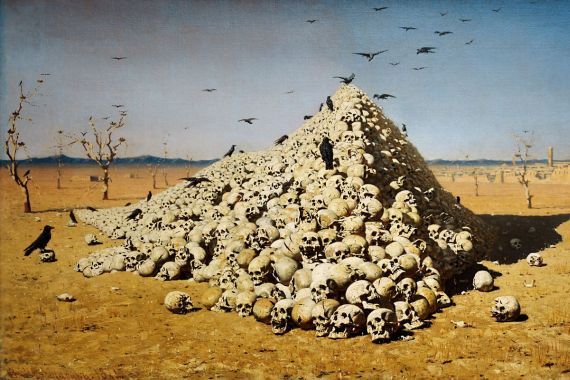

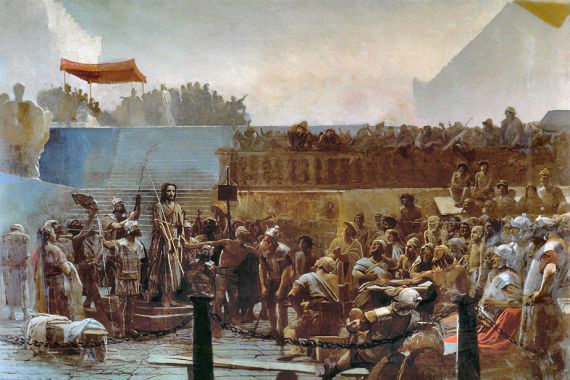

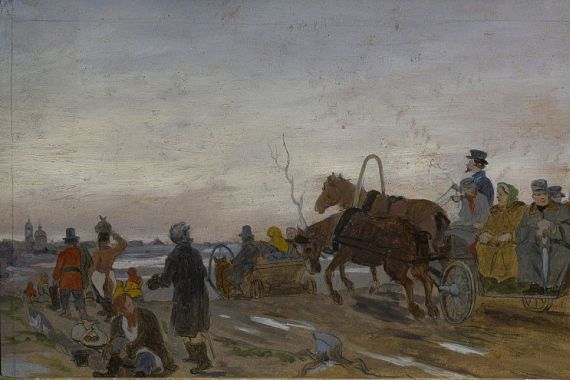

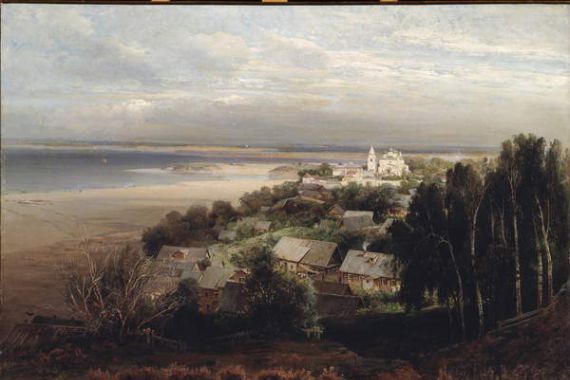

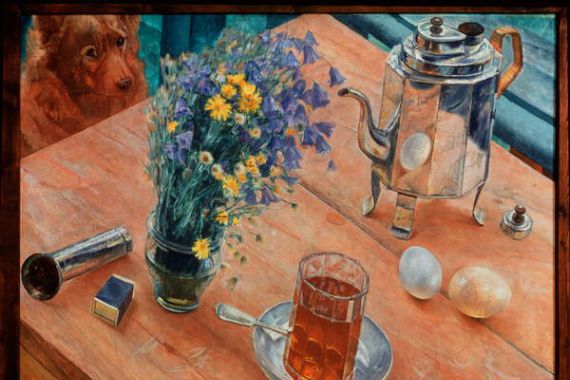

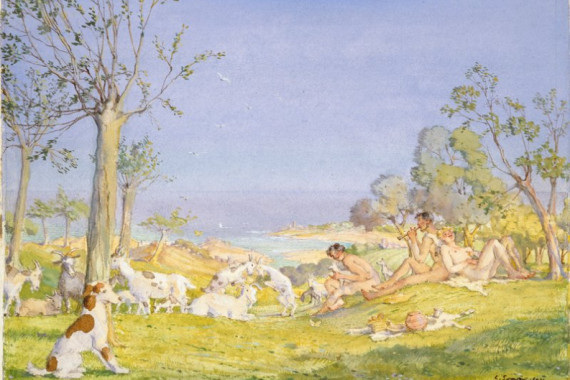

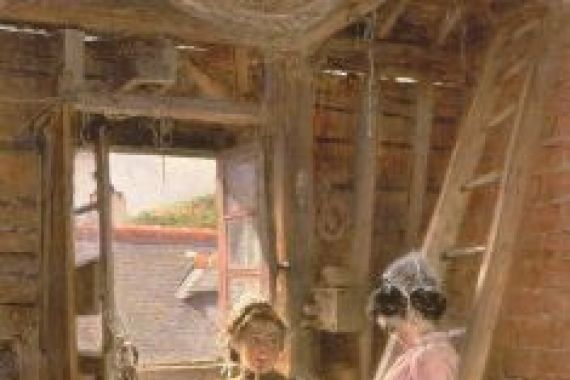

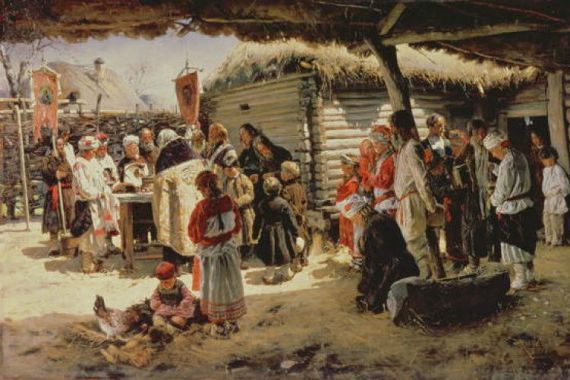

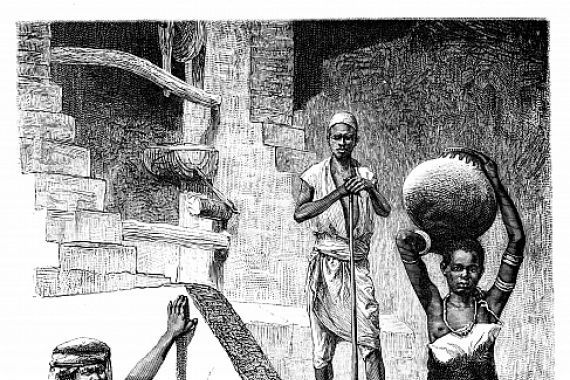

Russian painting is a kaleidoscope of longing, awakening and resistance. Anyone standing in front of a painting by Isaak Levitan, for example, senses the quiet power of the Russian landscape - not as a romantic idyll, but as an existential space in which man and nature meet. Levitan's "Above the Eternal Calm" is not just a landscape painting, but a quiet drama in which heaven and earth wrestle with each other. And then there are the portraits by Ilya Repin, which capture not just faces but entire life stories with almost photographic precision. Repin's "Wolgatreidler", for example, makes the exhaustion but also the dignity of ordinary people palpable - a picture that seems like a silent protest against social injustice.

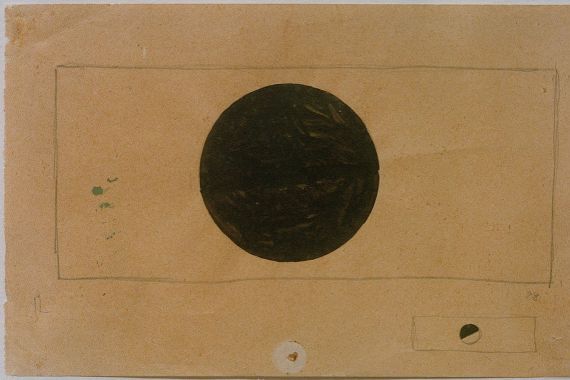

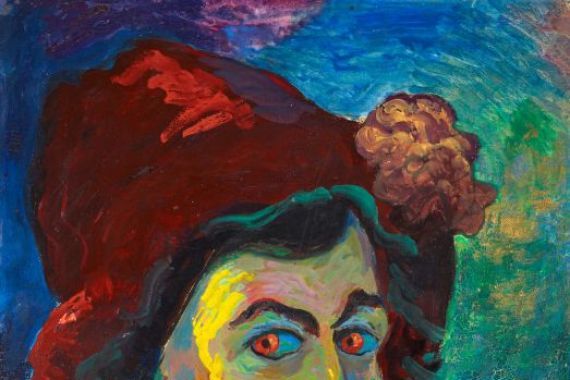

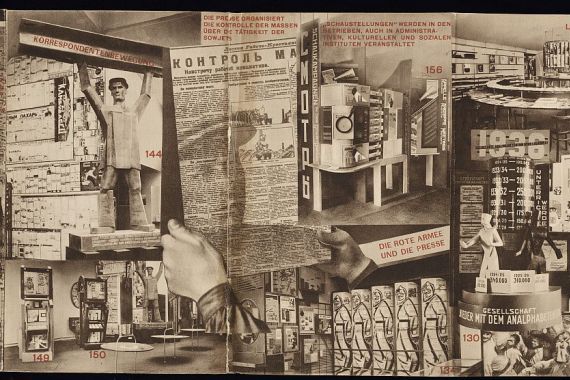

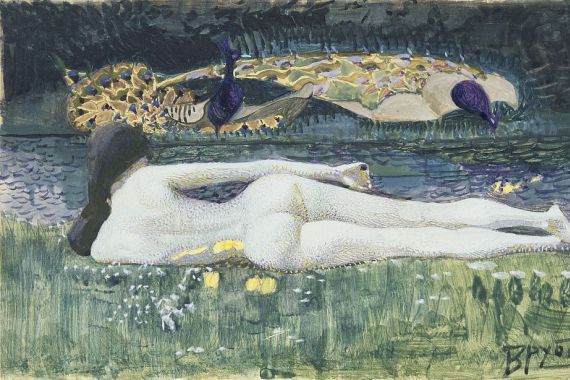

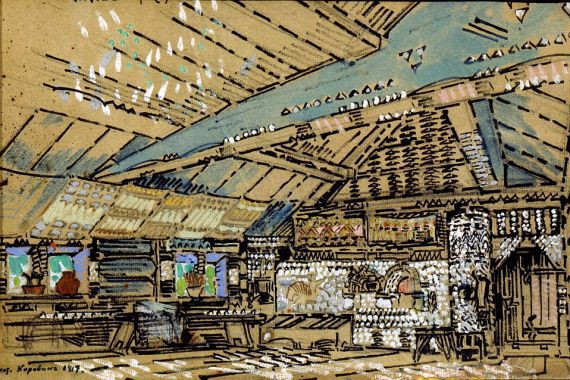

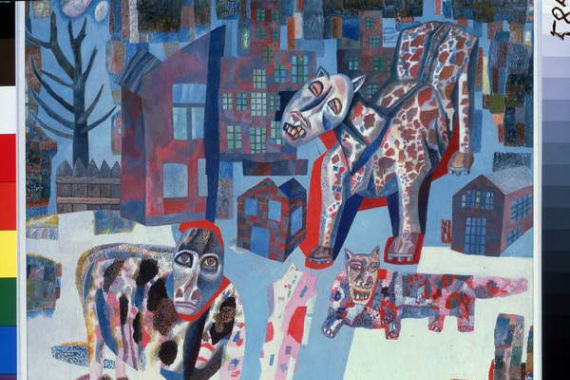

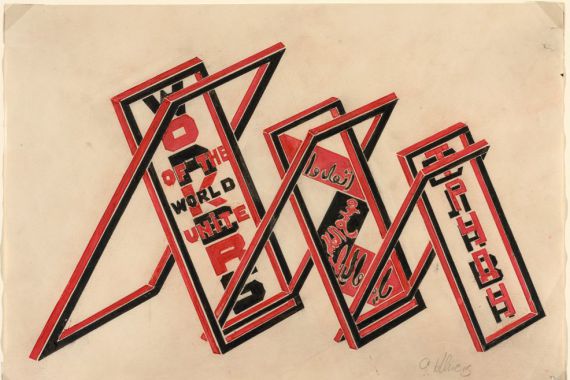

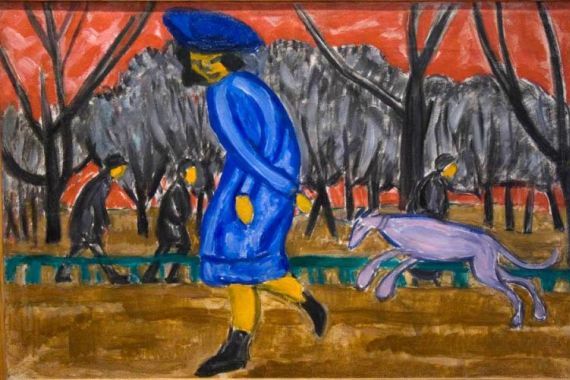

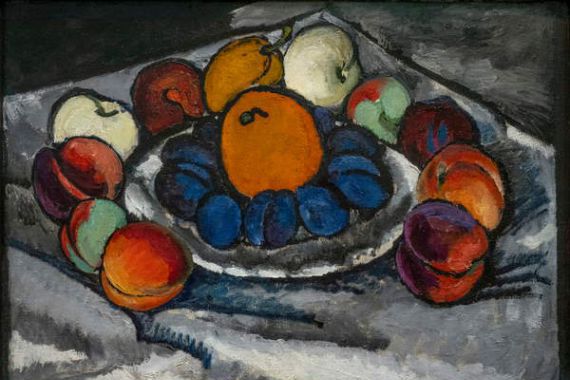

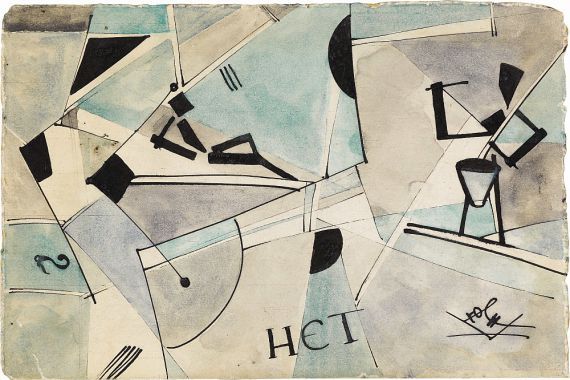

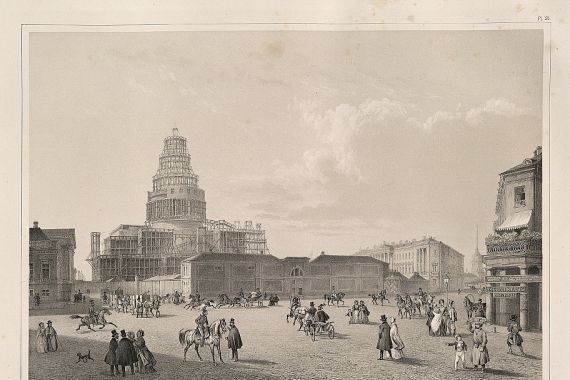

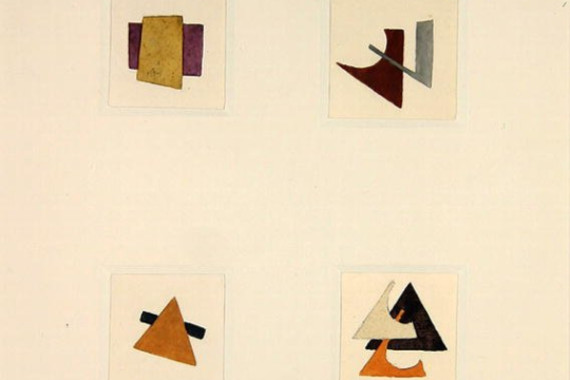

But Russian art is far more than realism. It is a field of experimentation and a stage for visionaries. The studios of Moscow and St. Petersburg were buzzing at the beginning of the 20th century: artists such as Kazimir Malevich dared to make a radical break with representationalism. His "Black Square" - a seemingly simple but revolutionary work - came to symbolise a new beginning, the search for a new, universal visual language. The Russian avant-garde, with names such as Natalia Goncharova and Lyubov Popova, broke the boundaries of the familiar, making colours dance and forms explode. Even in photography, for example with Alexander Rodchenko, the image became a field of experimentation for new perspectives and forms of expression.

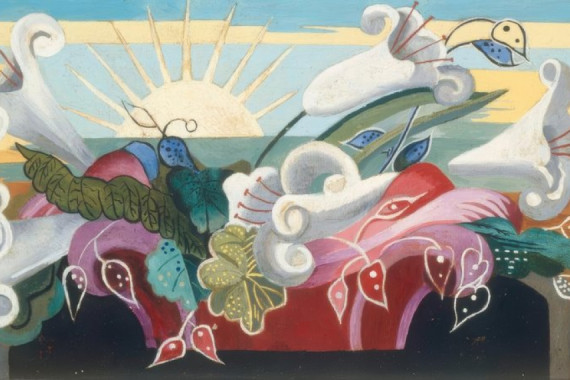

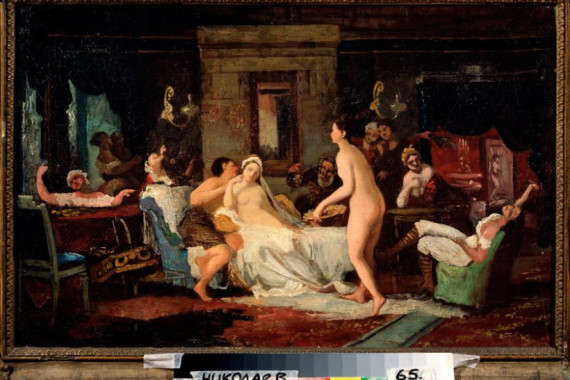

What makes Russian art so unique is its constant oscillation between tradition and revolution, between deep roots and bold vision. It is characterised by a longing for the absolute, for truth and beauty - and by an unshakeable power to create something new even under the most adverse conditions. Anyone who engages with Russian art is immersed in a world full of contrasts: Here, light and shadow, hope and despair, stillness and new beginnings come together. Every painting, every drawing, every photograph is a window into a soul that is as wide and deep as the country itself.

A soft mist lies over the endless expanses as I - a young painter driven by longing and curiosity - look at the Russian landscape for the first time. The air is permeated by a peculiar melancholy that covers the villages, forests and rivers like a veil. In Russia, it seems to me, art is never merely a reflection, but always a mirror of the soul, an echo of the mighty nature and the turbulent history. The colours I mix on my palette are heavy and rich, as if they wanted to capture the depth of the Russian earth - ochre, deep blue, the red of the setting sun. Here, where the winters are long and the summers are suffused with shimmering light, pictures are created that tell more than words ever could.

Russian painting is a kaleidoscope of longing, awakening and resistance. Anyone standing in front of a painting by Isaak Levitan, for example, senses the quiet power of the Russian landscape - not as a romantic idyll, but as an existential space in which man and nature meet. Levitan's "Above the Eternal Calm" is not just a landscape painting, but a quiet drama in which heaven and earth wrestle with each other. And then there are the portraits by Ilya Repin, which capture not just faces but entire life stories with almost photographic precision. Repin's "Wolgatreidler", for example, makes the exhaustion but also the dignity of ordinary people palpable - a picture that seems like a silent protest against social injustice.

But Russian art is far more than realism. It is a field of experimentation and a stage for visionaries. The studios of Moscow and St. Petersburg were buzzing at the beginning of the 20th century: artists such as Kazimir Malevich dared to make a radical break with representationalism. His "Black Square" - a seemingly simple but revolutionary work - came to symbolise a new beginning, the search for a new, universal visual language. The Russian avant-garde, with names such as Natalia Goncharova and Lyubov Popova, broke the boundaries of the familiar, making colours dance and forms explode. Even in photography, for example with Alexander Rodchenko, the image became a field of experimentation for new perspectives and forms of expression.

What makes Russian art so unique is its constant oscillation between tradition and revolution, between deep roots and bold vision. It is characterised by a longing for the absolute, for truth and beauty - and by an unshakeable power to create something new even under the most adverse conditions. Anyone who engages with Russian art is immersed in a world full of contrasts: Here, light and shadow, hope and despair, stillness and new beginnings come together. Every painting, every drawing, every photograph is a window into a soul that is as wide and deep as the country itself.

×