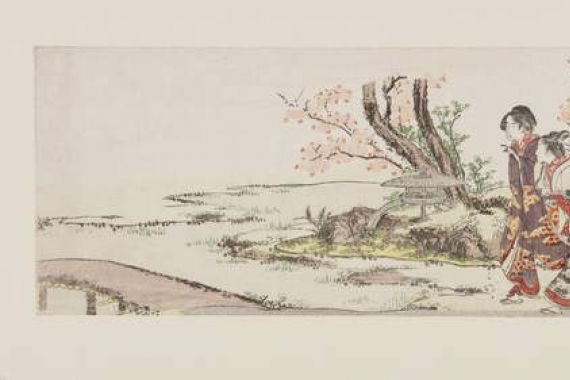

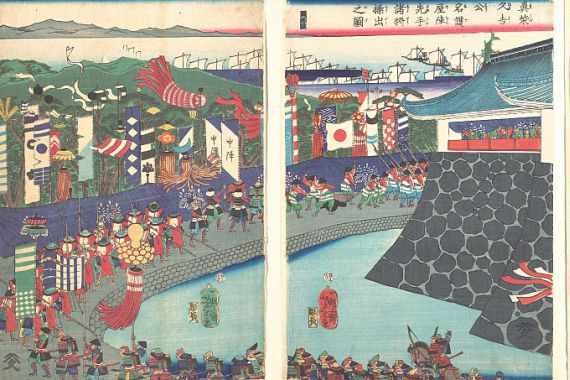

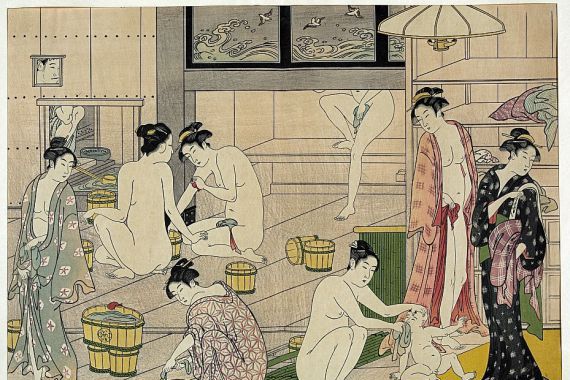

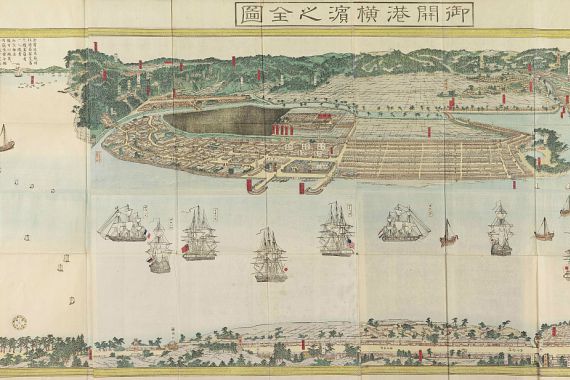

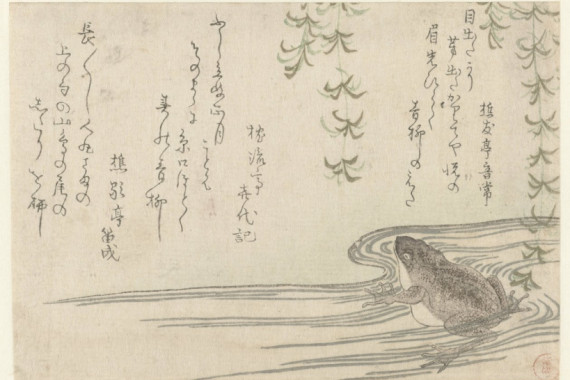

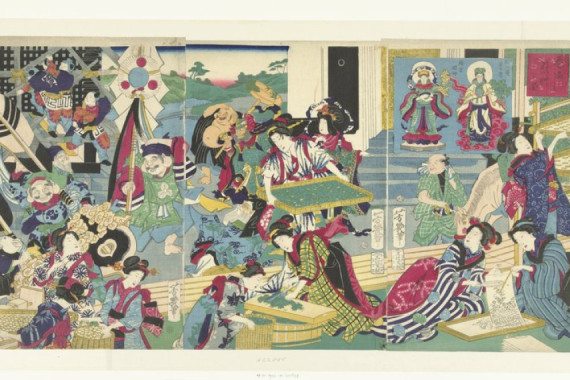

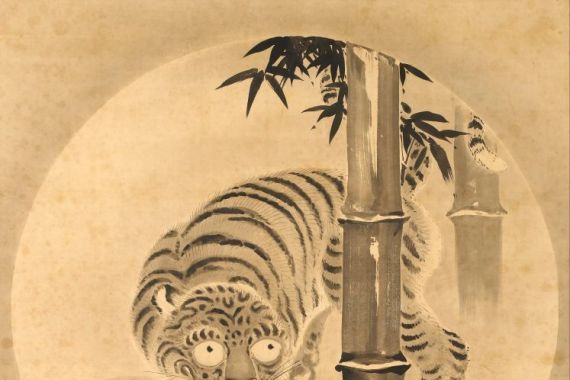

A soft rustling of paper, the gentle flow of ink on rice paper - this is how the history of Japanese painting begins, winding its way through the centuries like a silent river. While in Europe oil painting overwhelms the senses with dramatic light and opulent colour, Japanese art focuses on the unspoken, the allusive, that which lies between the lines. Japan's national history, characterised by long periods of isolation and sudden openings, is reflected in its art: it is a reflection of the balance between tradition and innovation, between closeness to nature and urban modernity.

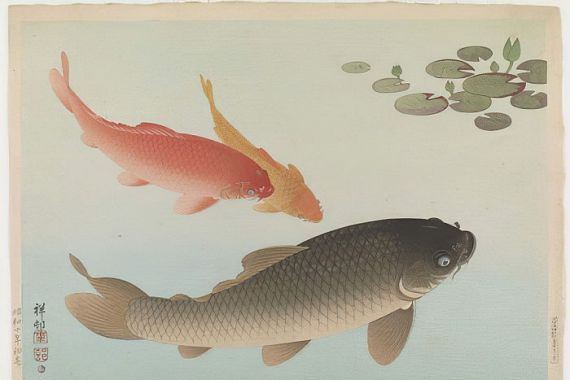

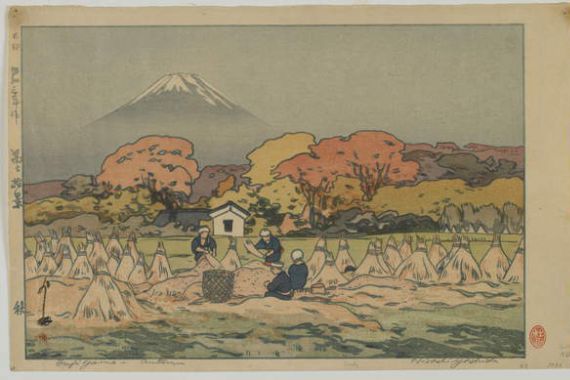

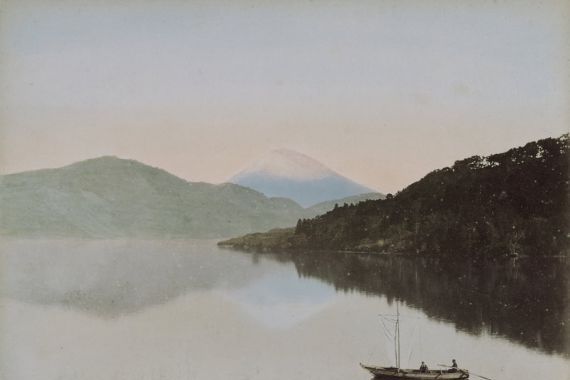

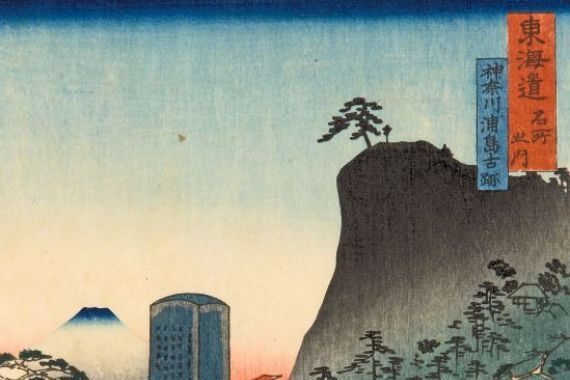

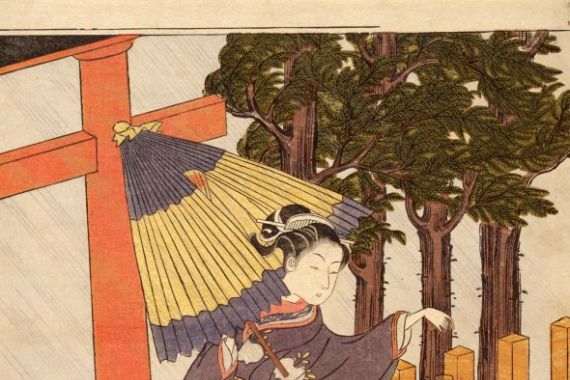

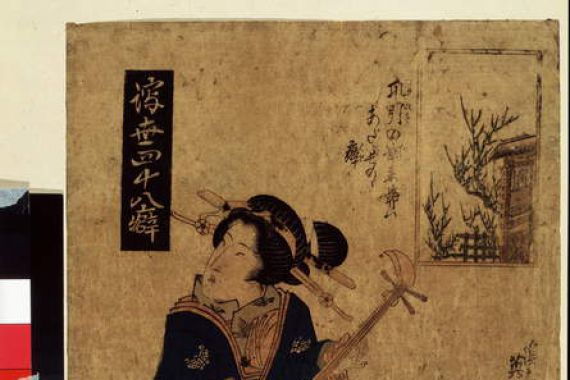

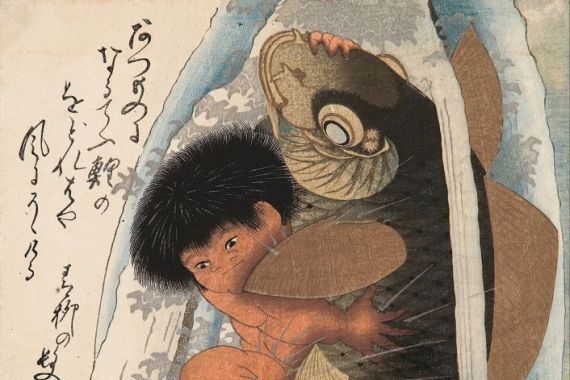

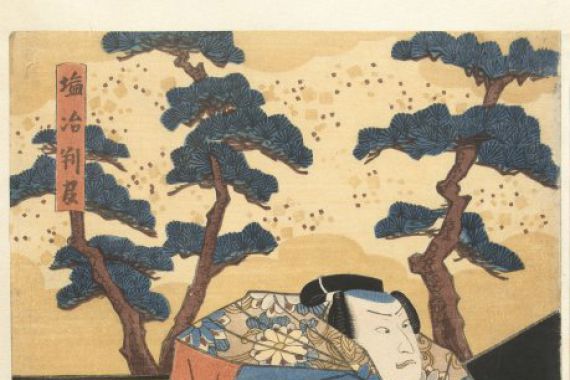

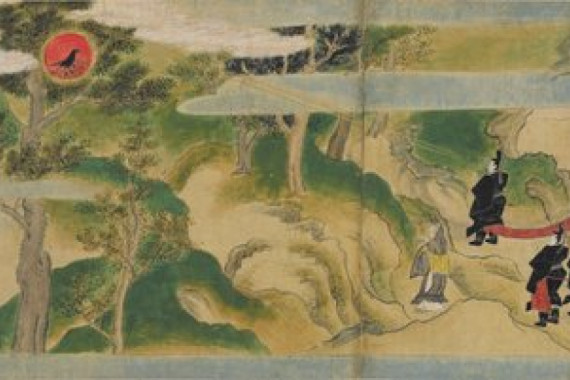

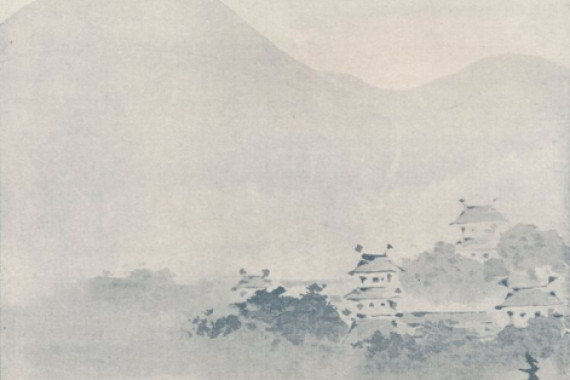

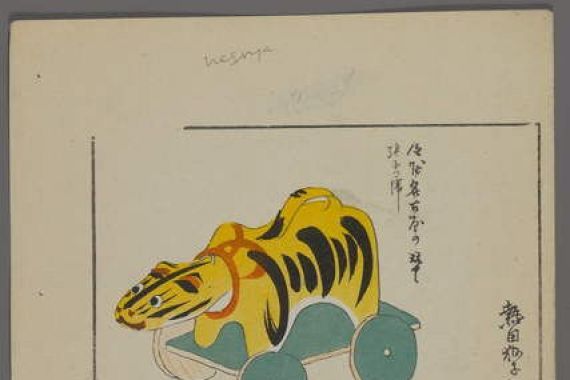

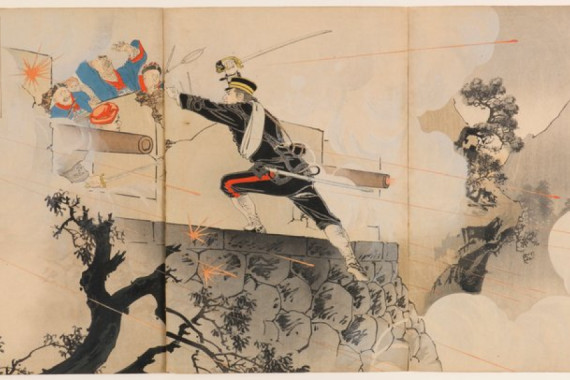

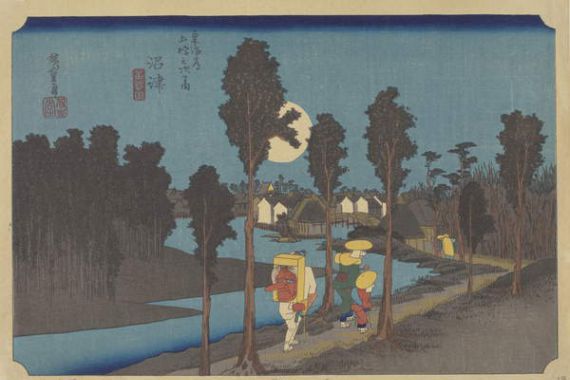

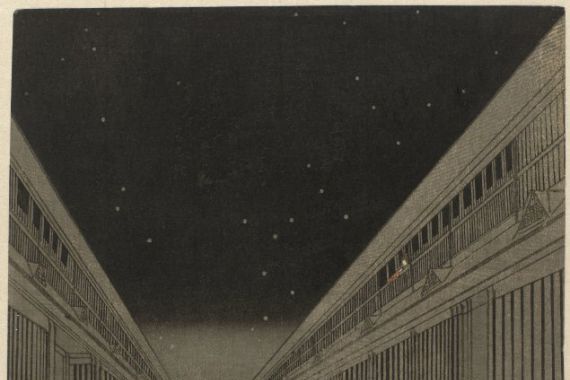

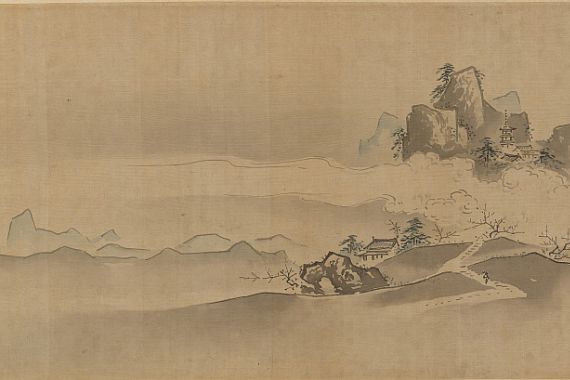

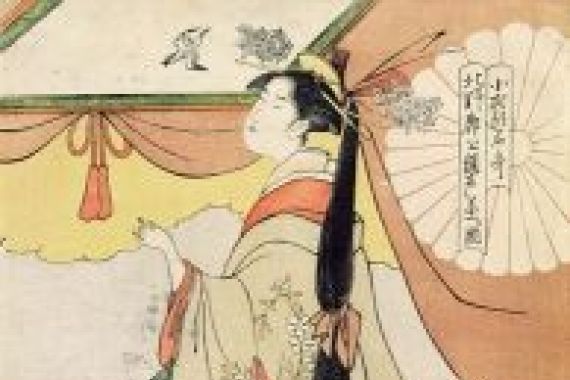

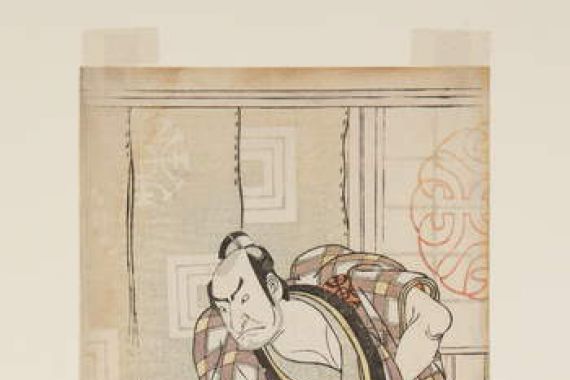

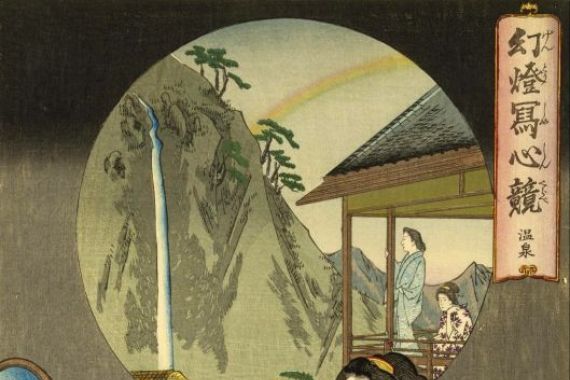

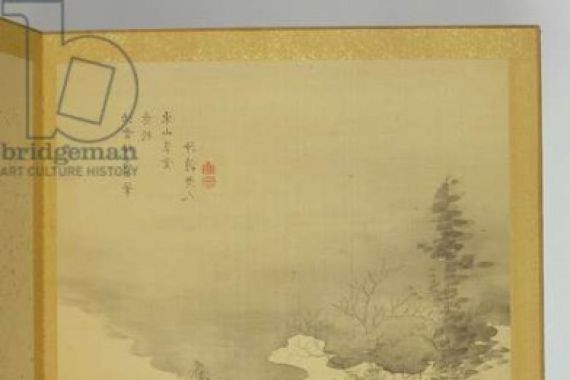

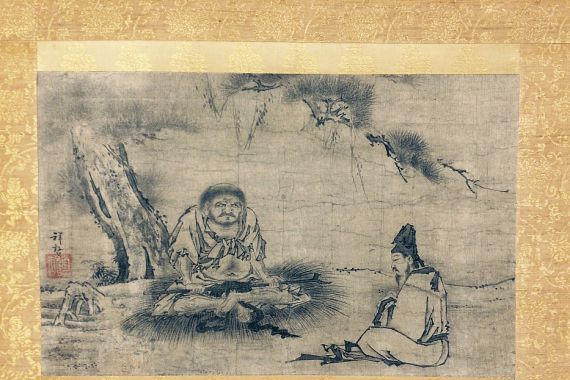

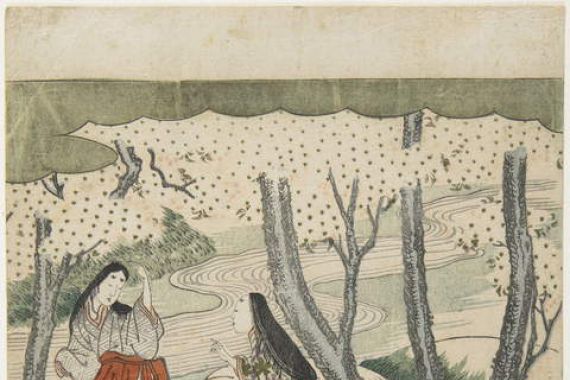

Imagine looking at an ukiyo-e woodcut by Hokusai: the "Great Wave off Kanagawa" towers up, powerful and yet full of elegance, while Mount Fuji appears almost shy in the background. Unlike the Italian Renaissance, which placed man at the centre, nature always remains the main protagonist in Japan. The artists - from Sesshū Tōyō, whose monochrome landscapes seem like meditations, to Hiroshige, who captures the fleetingness of the moment with his colour woodcuts - know how to celebrate the ephemeral, the transient. Even in 20th century photography, such as Daidō Moriyama, this sense of the ephemeral remains: Grainy black and white images that capture the pulsating life of Tokyo look like modern counterparts to the old woodcuts.

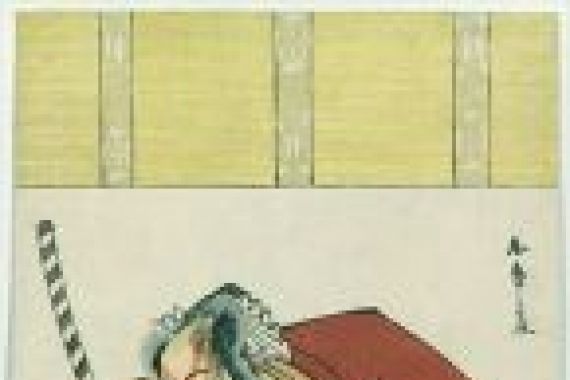

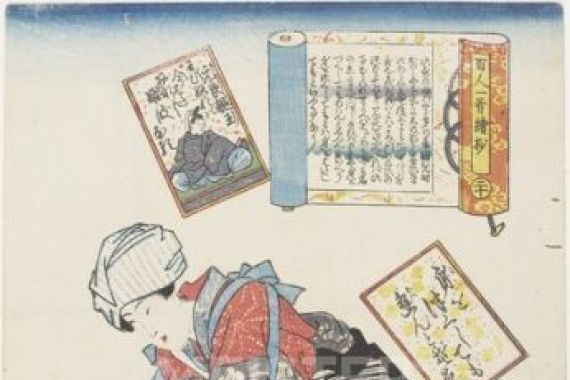

A surprising detail: the technique of the colour woodcut, which matured to perfection in Japan, later inspired the French Impressionists. Monet, van Gogh and Degas collected Japanese prints, studied the two-dimensional composition, the bold cut-outs and the reduction to the essentials. But while in France painting became a stage for light, in Japan it remained a place of stillness, of contemplation. Takeuchi Seihō's watercolours, for example, in which a single crane stands on a snow-covered ground, tell us more about the Japanese soul than a thousand words. And even today, in the contemporary art of Yayoi Kusama, the old patterns still flash up: Dots, repetitions, the play with emptiness and fullness - an echo of centuries-old aesthetics.

Anyone who engages with Japanese art enters a space in which the invisible is just as important as the visible. Here, the white of the paper becomes an ocean, the brushstroke a breath of wind, the motif a meditation. For art lovers and collectors of art prints, a world opens up in which every picture is an invitation to pause for a moment - and to discover the essential in the silence.

A soft rustling of paper, the gentle flow of ink on rice paper - this is how the history of Japanese painting begins, winding its way through the centuries like a silent river. While in Europe oil painting overwhelms the senses with dramatic light and opulent colour, Japanese art focuses on the unspoken, the allusive, that which lies between the lines. Japan's national history, characterised by long periods of isolation and sudden openings, is reflected in its art: it is a reflection of the balance between tradition and innovation, between closeness to nature and urban modernity.

Imagine looking at an ukiyo-e woodcut by Hokusai: the "Great Wave off Kanagawa" towers up, powerful and yet full of elegance, while Mount Fuji appears almost shy in the background. Unlike the Italian Renaissance, which placed man at the centre, nature always remains the main protagonist in Japan. The artists - from Sesshū Tōyō, whose monochrome landscapes seem like meditations, to Hiroshige, who captures the fleetingness of the moment with his colour woodcuts - know how to celebrate the ephemeral, the transient. Even in 20th century photography, such as Daidō Moriyama, this sense of the ephemeral remains: Grainy black and white images that capture the pulsating life of Tokyo look like modern counterparts to the old woodcuts.

A surprising detail: the technique of the colour woodcut, which matured to perfection in Japan, later inspired the French Impressionists. Monet, van Gogh and Degas collected Japanese prints, studied the two-dimensional composition, the bold cut-outs and the reduction to the essentials. But while in France painting became a stage for light, in Japan it remained a place of stillness, of contemplation. Takeuchi Seihō's watercolours, for example, in which a single crane stands on a snow-covered ground, tell us more about the Japanese soul than a thousand words. And even today, in the contemporary art of Yayoi Kusama, the old patterns still flash up: Dots, repetitions, the play with emptiness and fullness - an echo of centuries-old aesthetics.

Anyone who engages with Japanese art enters a space in which the invisible is just as important as the visible. Here, the white of the paper becomes an ocean, the brushstroke a breath of wind, the motif a meditation. For art lovers and collectors of art prints, a world opens up in which every picture is an invitation to pause for a moment - and to discover the essential in the silence.

×