A gust of wind carries the scent of fresh earth and damp grass through the open window of my studio in Lviv. I'm sitting in front of a blank canvas, but colours are already dancing in my head: the deep blue of the Dnipro, the bright yellow of the sunflower fields, the soft pink of dawn over the Carpathian Mountains. In Ukraine, art is never just a picture - it is an echo of the landscape, a mirror of the soul, a silent protest against oblivion. Here, where East and West meet, where tradition and modernity embrace and challenge each other, every watercolour, every sketch, every photograph is a piece of lived history.

Ukrainian art resembles a mosaic, composed of countless fragments: There is the expressive colourfulness of Mykola Pymonenko, whose rural scenes capture the lives of ordinary people with an almost poetic honesty. His oil paintings tell of festivals and field work, of hope and melancholy - and they do so with a directness that strikes the viewer right in the heart. But the art of Ukraine does not stop at the idyllic. It searches, it questions, it contradicts. In the works of Maria Prymachenko, whose gouaches are full of fantastic animals and bright ornaments, one senses the power of folk art, but also the courage to make her own mark. Her paintings, as naive as they may appear at first glance, are in fact a rebellion against confinement, a celebration of fantasy in times of political control.

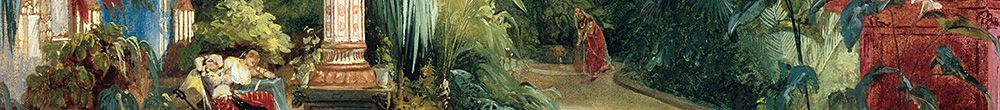

Sometimes a single picture is enough to grasp an entire era. The famous "Cossack Song" by Serhij Vasylkivsky, for example, a watercolour celebrating the freedom and pride of the Ukrainian Cossacks, became a symbol of national identity - and silent resistance to foreign rule. In the turmoil of the 20th century, when Ukraine was torn between the fronts of history, artists such as Oleksandr Bohomazov and Dawid Burliuk found new forms of expression: Their avant-garde compositions, often in the form of prints or collages, broke with old ways of seeing and sought a language for the inexpressible. Society changed, and so did art - it became more political, more experimental, sometimes even more desperate.

Finally, photography, this seemingly objective medium, became an instrument of remembrance and hope in Ukraine. The photographs of Boris Mykhailov, who documented post-Soviet Kharkiv in all its raw beauty, are more than mere images: They are testimonies to a country in transition, full of contradictions and longings. His pictures reflect the Ukrainian soul - vulnerable, proud, unbroken.

Ukrainian art is thus a constant dialogue between yesterday and today, between the individual and society. It tells of suffering and new beginnings, of home and foreign lands, of the inexhaustible power of images that say more than words. Anyone who engages with this art discovers not just a country, but a whole world of colours, shapes and stories - lively, surprising and deeply human.

A gust of wind carries the scent of fresh earth and damp grass through the open window of my studio in Lviv. I'm sitting in front of a blank canvas, but colours are already dancing in my head: the deep blue of the Dnipro, the bright yellow of the sunflower fields, the soft pink of dawn over the Carpathian Mountains. In Ukraine, art is never just a picture - it is an echo of the landscape, a mirror of the soul, a silent protest against oblivion. Here, where East and West meet, where tradition and modernity embrace and challenge each other, every watercolour, every sketch, every photograph is a piece of lived history.

Ukrainian art resembles a mosaic, composed of countless fragments: There is the expressive colourfulness of Mykola Pymonenko, whose rural scenes capture the lives of ordinary people with an almost poetic honesty. His oil paintings tell of festivals and field work, of hope and melancholy - and they do so with a directness that strikes the viewer right in the heart. But the art of Ukraine does not stop at the idyllic. It searches, it questions, it contradicts. In the works of Maria Prymachenko, whose gouaches are full of fantastic animals and bright ornaments, one senses the power of folk art, but also the courage to make her own mark. Her paintings, as naive as they may appear at first glance, are in fact a rebellion against confinement, a celebration of fantasy in times of political control.

Sometimes a single picture is enough to grasp an entire era. The famous "Cossack Song" by Serhij Vasylkivsky, for example, a watercolour celebrating the freedom and pride of the Ukrainian Cossacks, became a symbol of national identity - and silent resistance to foreign rule. In the turmoil of the 20th century, when Ukraine was torn between the fronts of history, artists such as Oleksandr Bohomazov and Dawid Burliuk found new forms of expression: Their avant-garde compositions, often in the form of prints or collages, broke with old ways of seeing and sought a language for the inexpressible. Society changed, and so did art - it became more political, more experimental, sometimes even more desperate.

Finally, photography, this seemingly objective medium, became an instrument of remembrance and hope in Ukraine. The photographs of Boris Mykhailov, who documented post-Soviet Kharkiv in all its raw beauty, are more than mere images: They are testimonies to a country in transition, full of contradictions and longings. His pictures reflect the Ukrainian soul - vulnerable, proud, unbroken.

Ukrainian art is thus a constant dialogue between yesterday and today, between the individual and society. It tells of suffering and new beginnings, of home and foreign lands, of the inexhaustible power of images that say more than words. Anyone who engages with this art discovers not just a country, but a whole world of colours, shapes and stories - lively, surprising and deeply human.

×