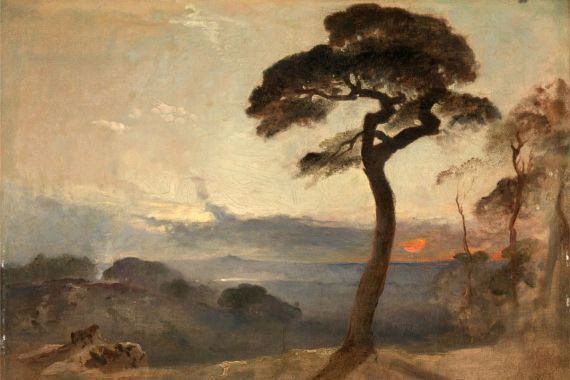

Imagine you are standing on a windswept cliff, the sea raging in a rich emerald green, and above you the light is rapidly changing through the clouds. This interplay of light and shadow, of melancholy and hope, is the heartbeat of Irish art. Ireland, the land of poets and rebels, has produced painting that is as multi-layered as its landscapes - and as surprisingly modern as its history allows. Irish art history is not a straightforward stream, but rather resembles a wild river that winds its way through the centuries, sometimes quiet and poetic, sometimes turbulent and full of drama.

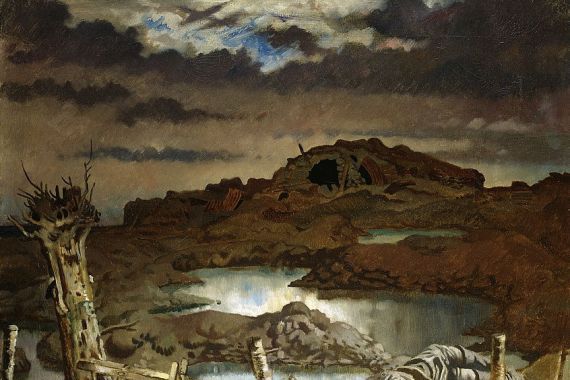

Those who follow in the footsteps of Irish painting first encounter a deep connection with nature. But unlike in classical European landscape painting, Irish light is never just a backdrop, but a protagonist. Paul Henry, for example, one of the most famous Irish painters, captured the raw beauty of the Connemara region in his oil paintings: Clouds drawn across the sky like heavy curtains, fields shimmering in a thousand shades of green and villages lying like splashes of colour in the vastness. His works are not mere images, but emotional maps that capture the feeling of life on an entire island. And yet Ireland's art is never just idyllic - it also knows the dark side. The watercolours by Jack B. Yeats, brother of the famous poet, are full of movement and drama, they tell of horse races and fairgrounds, but also of loneliness and longing. Yeats' expressive brushstrokes sometimes seem like hasty notes of a dream that is about to slip away.

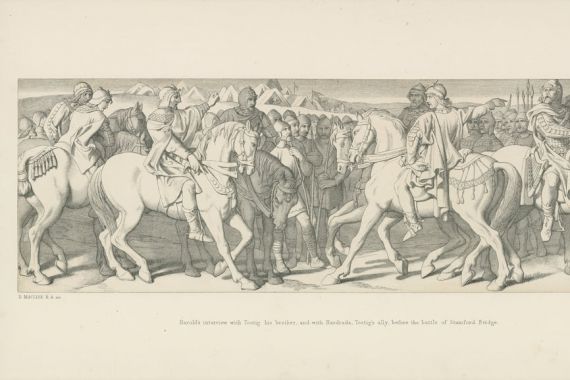

With the 20th century came a new generation of artists who no longer limited themselves to the visible. Mary Swanzy, for example, experimented with Cubism and Fauvism; her gouaches and oil paintings are visions of colour in which Ireland suddenly appears in bright tones and bold shapes. Irish artists also broke new ground in photography: Fergus Bourke captured urban Dublin in black and white, his photographs are snapshots of a society in transition, full of quiet melancholy and subtle irony. Printmaking, which for a long time led a shadowy existence, became a political medium through artists such as Robert Ballagh, reflecting Irish identity and history with pop art elements.

What makes Irish art so special is its ability to unite opposites: tradition and new beginnings, melancholy and joie de vivre, the local and the universal. In every brushstroke, in every photograph, in every sketch, you can sense the deep longing to belong - and at the same time the urge to constantly reinvent oneself. When you look at Irish art, you don't just see pictures, you feel the echo of an island that tells its stories with colours, light and lines. And perhaps it is precisely this echo that makes Irish art so irresistible - a whisper of wind and waves that lives on on paper and canvas.

Imagine you are standing on a windswept cliff, the sea raging in a rich emerald green, and above you the light is rapidly changing through the clouds. This interplay of light and shadow, of melancholy and hope, is the heartbeat of Irish art. Ireland, the land of poets and rebels, has produced painting that is as multi-layered as its landscapes - and as surprisingly modern as its history allows. Irish art history is not a straightforward stream, but rather resembles a wild river that winds its way through the centuries, sometimes quiet and poetic, sometimes turbulent and full of drama.

Those who follow in the footsteps of Irish painting first encounter a deep connection with nature. But unlike in classical European landscape painting, Irish light is never just a backdrop, but a protagonist. Paul Henry, for example, one of the most famous Irish painters, captured the raw beauty of the Connemara region in his oil paintings: Clouds drawn across the sky like heavy curtains, fields shimmering in a thousand shades of green and villages lying like splashes of colour in the vastness. His works are not mere images, but emotional maps that capture the feeling of life on an entire island. And yet Ireland's art is never just idyllic - it also knows the dark side. The watercolours by Jack B. Yeats, brother of the famous poet, are full of movement and drama, they tell of horse races and fairgrounds, but also of loneliness and longing. Yeats' expressive brushstrokes sometimes seem like hasty notes of a dream that is about to slip away.

With the 20th century came a new generation of artists who no longer limited themselves to the visible. Mary Swanzy, for example, experimented with Cubism and Fauvism; her gouaches and oil paintings are visions of colour in which Ireland suddenly appears in bright tones and bold shapes. Irish artists also broke new ground in photography: Fergus Bourke captured urban Dublin in black and white, his photographs are snapshots of a society in transition, full of quiet melancholy and subtle irony. Printmaking, which for a long time led a shadowy existence, became a political medium through artists such as Robert Ballagh, reflecting Irish identity and history with pop art elements.

What makes Irish art so special is its ability to unite opposites: tradition and new beginnings, melancholy and joie de vivre, the local and the universal. In every brushstroke, in every photograph, in every sketch, you can sense the deep longing to belong - and at the same time the urge to constantly reinvent oneself. When you look at Irish art, you don't just see pictures, you feel the echo of an island that tells its stories with colours, light and lines. And perhaps it is precisely this echo that makes Irish art so irresistible - a whisper of wind and waves that lives on on paper and canvas.

×